Michael Morrow, PhD - Arcadia University

Evidence-based practice (EBP) in clinical and counseling psychology is both an ethical and social justice imperative. Clients of all backgrounds deserve the psychosocial treatments most likely to benefit them and not cause harm (Lilienfeld, 2007). Accordingly, graduate programs are charged to provide students with sufficient preparation in EBP. Ideally, students should graduate their programs with a clear understanding of EBP, emerging skills in empirically supported assessments and treatments, and a firm commitment to maintaining an evidence-based orientation throughout their careers (Morrow, Lee, Bartoli, & Gillem, 2016). While graduates will undoubtedly require further training to master EBP, their education should plant the seeds needed to later bloom into competent evidence-based practitioners.

As a clinical psychologist (reared in a clinical science program) and a counselor educator, I am tasked with the privilege and challenge of helping MA-level counseling students begin their transformation into evidence-based practitioners, all in roughly three years of coursework and applied training. MA-level practitioners comprise the bulk of frontline mental healthcare in many communities (Weisz, Chu, & Polo, 2004); thus, it is critical to provide them with strong training in EBP. Over the past five years, I have learned that guiding students toward competence in EBP is no easy feat; in fact, simply helping them grasp the meaning of EBP is a major challenge, especially in light of the many misinterpretations that plague the field.

While definitions have evolved over time, EBP currently represents a broad framework for clinical decision making and service based on three key components: the strongest available research, clinical expertise, and client characteristics (e.g., preferences, strengths, and culture; Kazdin, 2008). When (and only when) these three components are thoughtfully and continually integrated throughout treatment, EBP occurs. Recent models also emphasize the role of the therapeutic relationship and other common factors (Ackerman et al., 2001).

Unfortunately, many students fail to internalize EBP as an overarching orientation and reduce it solely to using empirically supported treatments (ESTs): interventions supported by rigorous research for particular disorders (Norcross & Karpiak, 2012). While EBP involves using ESTs, it is a broader framework for decision making and intervention. This tendency to minimize EBP to ESTs is well documented (Luebbe, Radcliffe, Callands, Green, & Thorn, 2007) and poses a significant barrier to the proliferation of EBP. Creative teaching strategies are needed to ensure that students acquire a fuller and more accurate understanding of EBP.

Learning theory and research indicate that metaphors can be powerful teaching tools (Hansen, Richland, Baumer, & Tomlinson, 2011). Recently, I developed a metaphor to introduce EBP to counseling students. As a novice painter, I liken EBP to oil painting. I start by explaining that artists utilize a variety of tools (brushes, paint knives, and palettes) to mix and apply various materials (gesso, paint, and varnish); these tools and materials are analogous to practitioners’ knowledge and skills, including their competence in making evidence-based decisions, building strong therapeutic alliances, conducting and interpreting assessments, and delivering specific interventions (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy or exposure and response prevention).

I then add to the metaphor the adoption of an evidence-based orientation. Artists often begin oil paintings by covering the whole canvas with a wash of acrylic paint (e.g., a flat layer of light blue acrylic paint). While numerous layers of paint will be added atop, this wash provides an underlying tone for the entire piece (i.e., the blue wash will interact with each new layer of paint). This acrylic wash represents the adoption of an overarching evidence-based orientation, a guiding framework that colors key clinical decisions, such as choosing assessment tools, formulating conceptualizations, selecting treatment modalities, tailoring interventions, and monitoring progress. To illustrate this point, I ask students to visualize a blank treatment plan and imagine painting “EBP” in a light hue across the background (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Next, I add to the metaphor the process of utilizing research to guide treatment planning. Once the acrylic wash has dried, artists add their first layer of oil paint, which typically blocks out major forms (e.g., a flat grey patch denoting a mountain range) and creates a basic composition for the piece. Regarding EBP, this first layer reflects evidence from the best available research (Lilienfeld et al., 2013). When the research base is strong for treatments targeting a particular condition, it offers a very clear picture for treatment.

Next, I add to the metaphor the process of utilizing research to guide treatment planning. Once the acrylic wash has dried, artists add their first layer of oil paint, which typically blocks out major forms (e.g., a flat grey patch denoting a mountain range) and creates a basic composition for the piece. Regarding EBP, this first layer reflects evidence from the best available research (Lilienfeld et al., 2013). When the research base is strong for treatments targeting a particular condition, it offers a very clear picture for treatment.

For instance, when working with a child with significant disruptive behavior, rigorous efficacy studies deem behavioral parent training a well-established intervention (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). In this example, students can visualize themselves painting “behavioral parent training” atop a treatment plan already washed in a background of EBP (Figure 2). However, when research is lacking (e.g., ESTs for child Adjustment Disorders), it provides a much fainter picture of treatment. In these cases, practitioners must rely more heavily on the other components of EBP: clinical expertise and client characteristics.

Figure 2

I next introduce practitioners’ use of clinical expertise. Artists then add additional layers of oils and other materials (varnish, sand, stones) atop the previous layers to achieve various effects (detail, contrast, texture, depth, shine). Relative to EBP, these new layers reflect the integration of practitioners’ professional expertise to fill in any major gaps left uncovered by the extant research. In working with a child with an Adjustment Disorder, a practitioner could draw from her experience working with youth with this disorder or similar symptomology. If the child is presenting with a mix of internalizing symptoms, the practitioner could utilize well-established treatments (e.g., cognitive behavior therapies) for pediatric anxiety or depression.

I next introduce practitioners’ use of clinical expertise. Artists then add additional layers of oils and other materials (varnish, sand, stones) atop the previous layers to achieve various effects (detail, contrast, texture, depth, shine). Relative to EBP, these new layers reflect the integration of practitioners’ professional expertise to fill in any major gaps left uncovered by the extant research. In working with a child with an Adjustment Disorder, a practitioner could draw from her experience working with youth with this disorder or similar symptomology. If the child is presenting with a mix of internalizing symptoms, the practitioner could utilize well-established treatments (e.g., cognitive behavior therapies) for pediatric anxiety or depression.

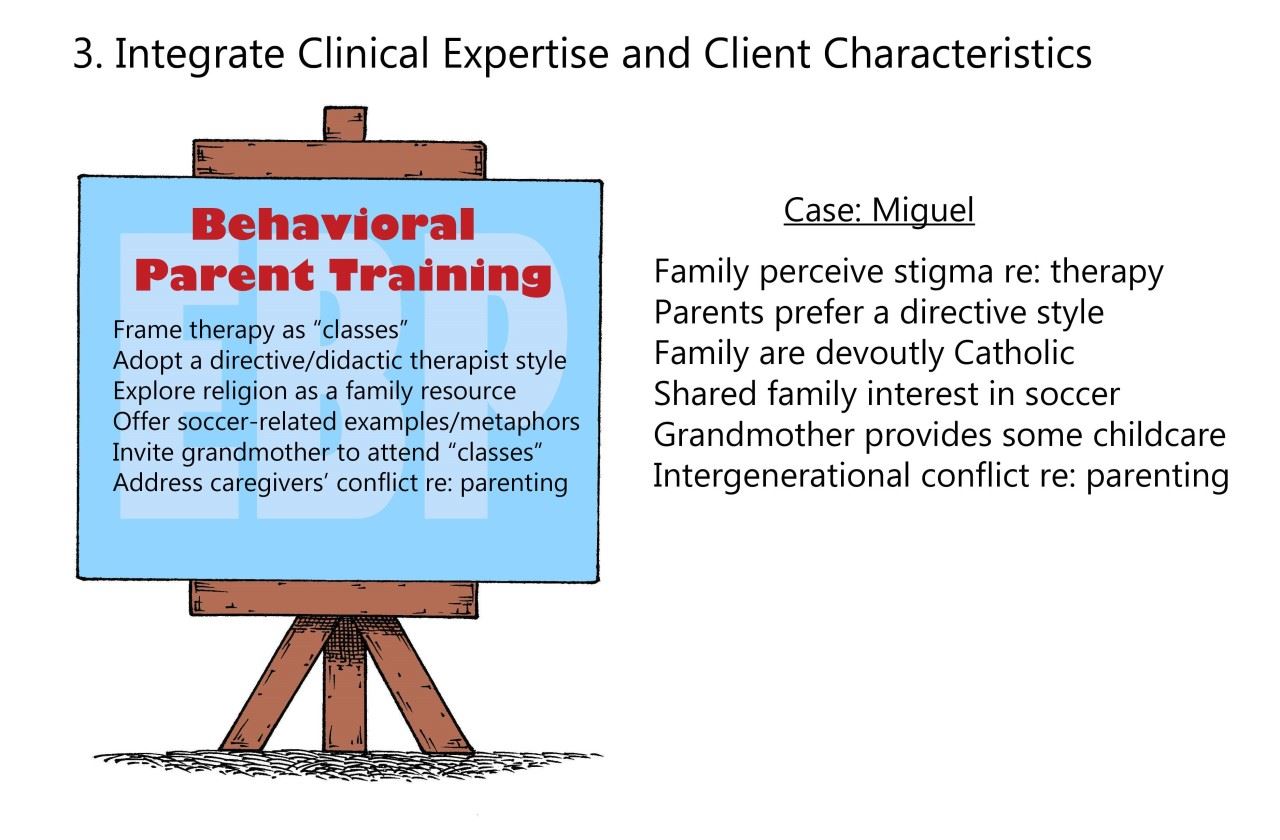

Moreover, the final layers reflect practitioners’ efforts to incorporate client characteristics into treatment. In discussing this topic, it is critical to distinguish “modifying” and “tailoring” treatments. When modifying, practitioners alter treatment in a substantial way (e.g., removing elements or delivering components out of sequence). While such modifications can be justified (Lindhiem, Bennett, Trentacosta, & McLear, 2014), evidence-based practitioners are more likely to tailor by infusing client characteristics into the treatment framework (e.g., offering examples to match clients’ interests and building upon clients’ resources and values to help them reach their goals; Figure 3). This process reflects the notion of “breathing life” into an evidence-based protocol (Kendall, Chu, & Gifford, 1998), and, in my opinion, represents the precise point where the science and art of therapy intersect in the context of EBP.

Figure 3

Finally, I tack two remaining concepts onto the metaphor: progress monitoring and objective thinking. Artists frequently step back to view their work from afar (and from various angles). Similarly, evidence-based practitioners repeatedly examine clients’ progress by carefully monitoring changes in symptoms and behaviors. Stepping back to evaluate the full course of treatment offers invaluable information to further case conceptualization and treatment planning. Moreover, viewing a painting from different angles is analogous to considering alternate plausible hypotheses (e.g., reevaluating the primary factors maintaining a problematic behavior), which is critical to avoiding errors in clinical judgment (Spengler & Strohmer, 1994).

Finally, I tack two remaining concepts onto the metaphor: progress monitoring and objective thinking. Artists frequently step back to view their work from afar (and from various angles). Similarly, evidence-based practitioners repeatedly examine clients’ progress by carefully monitoring changes in symptoms and behaviors. Stepping back to evaluate the full course of treatment offers invaluable information to further case conceptualization and treatment planning. Moreover, viewing a painting from different angles is analogous to considering alternate plausible hypotheses (e.g., reevaluating the primary factors maintaining a problematic behavior), which is critical to avoiding errors in clinical judgment (Spengler & Strohmer, 1994).

As paintings evolve with each brush stroke, the initial acrylic wash remains a unifying foundation for the entire work, just as an evidence-based orientation should guide the entire course of treatment. While I have experienced some success with this metaphor, I encourage other educators to develop their own based on their personal interests (e.g., sport, dance, music, cooking). Further, it would be helpful to start a field-wide dialogue on methods for teaching EBP, perhaps via a dedicated listserv or even an edited volume of different pedagogical approaches. Finally, I challenge all graduate instructors to guide their students to practice teaching others about EBP in order to prepare them to “carry the torch” from their education into the mental health landscape and paint their own pictures of EBP.

Ackerman, S. J., Benjamin, L. S., Beutler, L. E., Gelso, C. J., Goldfried, M. R., Hill, C., et al. (2010). Empirically supported therapy relationships: Conclusions and recommendations for the Division 29 Task Force. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 495-497.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215-237.

Hansen, J., Baumer, E. P. S., Richland, L., & Tomlinson, B. (2011). Metaphor and creativity in learning science. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Educational Researchers Association, New Orleans, LA.

Kazdin, A. E. (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63, 146-159.

Kendall, P. C., Chu, B., & Gifford, A. (1998). Breathing life into a manual: Flexibility and creativity with manual-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 5, 177-198.

Lindhiem, O., Bennett, C. B., Trentacosta, C. J., & McLear, C. (2014). Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 506-517.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2007). Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 53-70.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ritschel, L. A., Cautin, R. L., & Latzman, R. D. (2013). Why many practitioners are resistant to evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: Root causes and constructive remedies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 883-900.

Luebbe, A. M., Radcliffe, A. M., Callands, T. A., Green, D., & Thorn, B. E. (2007). Evidence-based practice in psychology: Perceptions of graduate students in scientist practitioner programs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 643-655.

Morrow, M. T., Lee, H., Bartoli, E., & Gillem, A. (2016). Strengthening counselor preparation in evidence-based practice. Submitted to the International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling.

Norcross, J. C., & Karpiak, C. P. (2012). Teaching clinical psychology: Four seminal lessons that all can master. Teaching of Psychology, 39, 301-307.

Spengler, P. M. & Strohmer, D. C. (1994). Counselor complexity and clinical judgment: Challenging the model of the average judge. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41, 1-10.

Published July 23, 2016